In a previous article I discussed how the historical geopolitical situation in Portugal (and, indirectly, its colonies) had a huge impact on the national wine industry during the 20th Century. This piece more or less picks up where the other left off, as we take a look at the what the future might hold. There are some significant changes already underway, and the driving force that is physically reshaping our viticultural landscape is without a doubt powered by changing climatic patterns. Global warming is set to have an even greater impact on Portuguese (and of course international) wine production in this century than Salazar did in the last.

Since the early 2000s, viticulture has been described as the 'canary in the coalmine' for global agriculture - feeling the effects earlier and more acutely than other cultures. According to Dr Jamie Goode, the wine industry is “exquisitely sensitive to climate change”.

Unlike most agricultural products, great wine vintages are always referred to by the year of their harvest. A unique set of conditions fortuitously combines to turn good grapes into stellar ones. Perfection is born of the coincidence of infinite details. But tiny changes to one or two of these external factors upset the outcome disproportionately - so no matter how good your viticulture and winemaking might be, you can't get there if the weather is against you.

Over a series of articles we now break down climate change into three main topics, and look in turn at the evidence, the effects and the possible solutions for the Portuguese wine industry. This is not yet another scientific article (and there are plenty of important ones already out there) but a series of snapshots from my own experience as a viticulturist and winemaker. These are some of the changes I have seen, the problems they are causing us on the frontline, and the solutions that we have tried to come up with.

First then, Part 1 - the evidence:

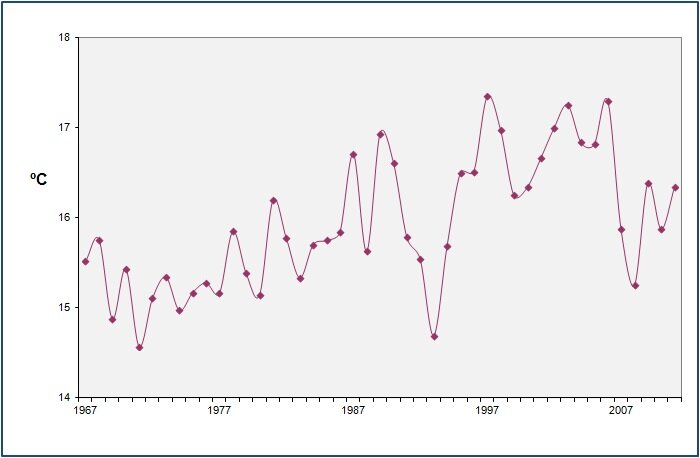

This graph uses records from a weather station in a vineyard in the Douro valley to show the average annual temperature from 1967 to 2011. Whilst annual averages are a slightly crude way of quantifying climate change, there is an undeniable tendency for temperatures to increase from left to right. Furthermore, in recent years there also appears to be much greater variation, with bigger fluctuations between years.

In some aspects these fluctuations are harder on the vines than consistent tiny incremental changes which would give us a better chance of adapting cultural processes to mitigate their effects over a sustained period.

Now let's see what happens when we superimpose the best fit line on the graph:

That is correct. On average the temperature in this vineyard has increased by 1.7º C in just 44 years. The United Nations climate change goal is to restrict global temperature increase to well below 2º C this century. Just saying.

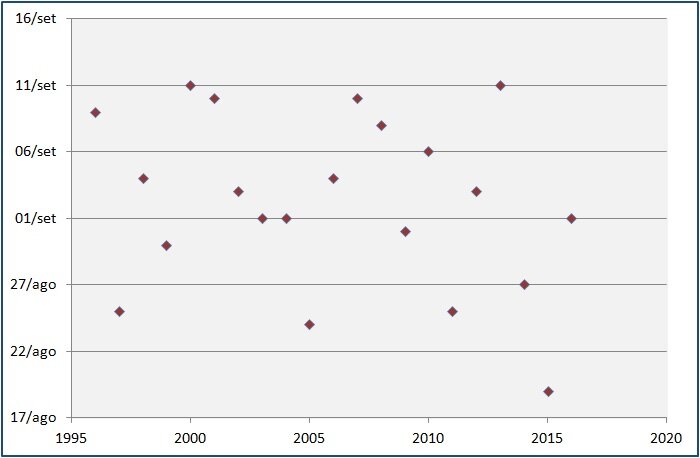

Warmer temperatures are generally associated with faster ripening (but not always - extreme heat causes the vines to shut down completely and maturation is therefore suspended). But if the grapes ripen sooner then the harvest needs to start earlier. The first day of the vintage coming in late August is now commonplace, where once mid-September was far more likely.

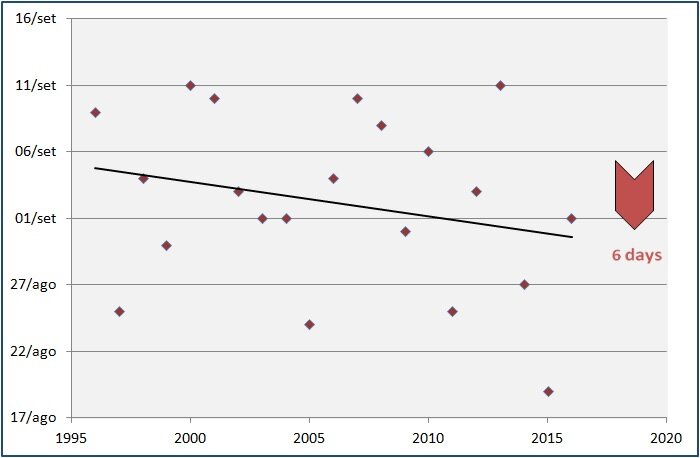

The graph above is from a vineyard in the Alentejo. It shows the date on which the first grapes were picked each harvest over a 21 year period. Now let's add the trend line:

We've gained nearly a week in ripening time. In fact, extrapolating from an admittedly small sample, for each year that goes by the grapes are getting ripe seven hours earlier than the year before.

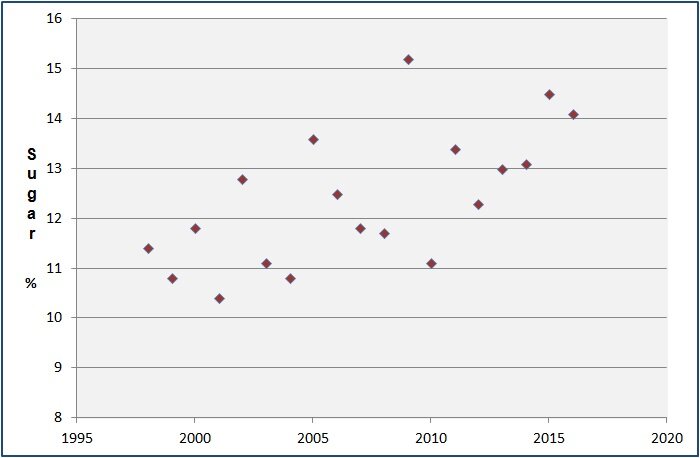

Another way of looking at this phenomenon is to compare grape samples of the same variety taken on the same date each year. Below I've shown this data from the same Alentejo vineyard over the same period. These are samples of Aragonês, all picked within a day or two of 20th August.

Technical note: I've called the vertical scale 'Sugar %' but actually it's a measure of sweetness called Baumé. The sweeter the grapes, the more alcohol they will produce during fermentation. The Baumé scale gives an approximation of what percentage alcohol wine will result for any given grape sugar level. So if we look at the very first point on the left of the graph, then had we harvested those grapes at that moment they would have produced a wine with about 11.5 % alcohol.

By now you've probably realised how much I like to average out data points with a best-fit line, so here it is:

I need to be quite clear here: that 2.9 % increase is not relative to our starting point. It is an absolute increase of nearly three percent probable alcohol in the finished wine. A wine that would have had 11 % alcohol in the mid '90s would now have nearly 14 % alcohol if it were made 20 years later. That's quite a headache, both literally and metaphorically.

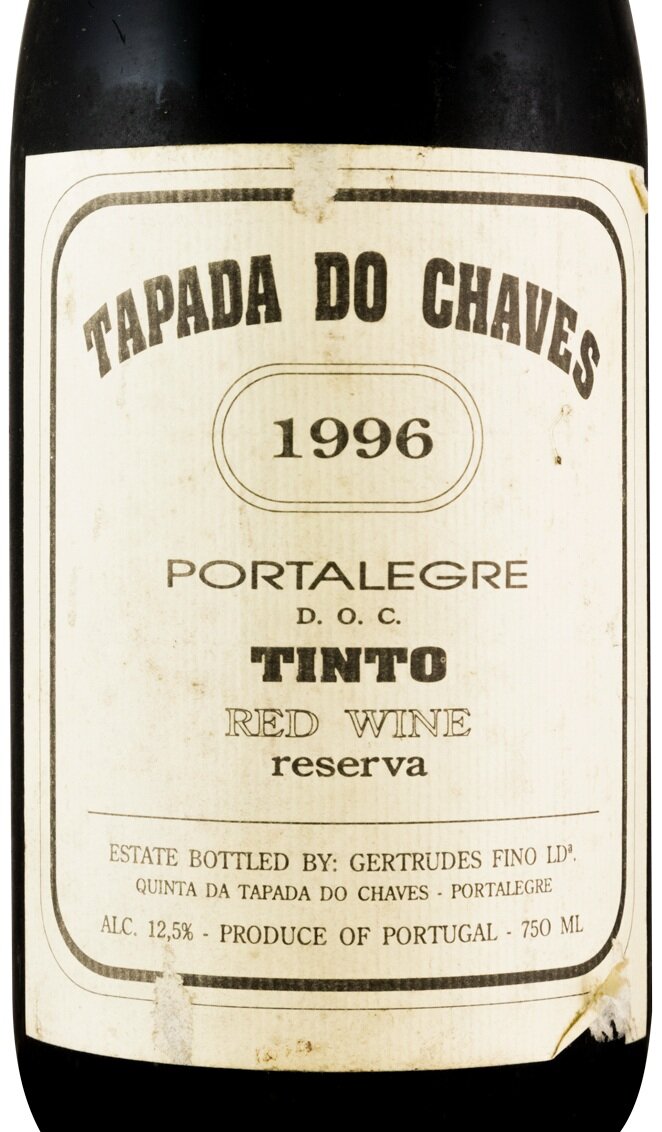

Last year I visited a winery near Portalegre. This is significant because the vineyards grow in the foothills of the Serra de São Mamede, making it the highest and coolest of the Alentejo wine growing sub-regions. As we will see in the third part of this series of articles, relocating vineyards to cooler places has been suggested as one of the best ways of mitigating the effects of climate change. So I asked the viticulturist what he thought. Like me, he had noticed very significant changes since he started working there in the late '90s. This is the wine they made during his first harvest:

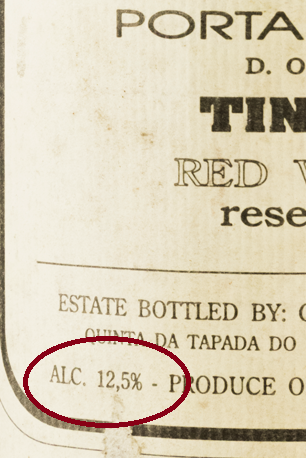

Have a look at the alcohol level.

And this was the current release that we tasted that day:

The 2.5 % difference in alcohol is almost identical to the effect I had found in the previous example.

This first section of this blog is about the evidence for climate change, and it seems to be undeniable.

Rising temperatures - check.

Earlier harvest dates - check.

Increasing sugar levels in the grapes - check.

More alcoholic wines - check.

The next section looks at the effects (mostly problematic, it must be said) that these various factors are having for the wine industry as a whole.